Critical Thinking Day 5: The Decision Making Process

- Chris Weinkauff Duranso

- Oct 23, 2020

- 10 min read

You may be thinking: "Do I really need to read a blog about how to make a decision?"

I don't blame you.

When I first started teaching critical thinking to college students, I was surprised at how much they had to learn, but also how I had a few lessons to learn, too!

Decision making is not a skill we are typically taught explicitly, which is really problematic and might be at the core of some of the societal issues we are facing today. That is another topic for another day. Today's topic is the psychological research on the process of making good decisions. This is not about what I think are the good decisions to be made, just about the process.

The larger the decision, or the larger the impact the decision may have on your life, the more important it is to take your time in the decision making process. Regret can suck the life out of you, literally (research says regret can reduce your life satisfaction and contribute to a shorter lifespan).

Experiencing post-decision dissonance (emotional or cognitive discomfort) is a common experience when the decision you made doesn't go as well as you had hoped. If you rush to make a decision, or fail to follow a strong decision making process, your post-decision dissonance can be even stronger, as you wrestled with regret over the process or lack of process used. If you work hard to follow the decision making process, and things still don't go as you had hoped, at least you can acknowledge that you did your best to make a good decision. After all, even when we spend a lot of time and effort in the decision making process, chance still happens. There are no guarantees in life!

So....One really great way to avoid regret and post-decision dissonance is to invest in the decision making process, taking your time in doing so.

The best way to work through the decision making process is to write things down. That way, you can go back to previous steps for reference. You will probably need to do that!

Here we go:

Frame the decision. Stating what the decision (or problem) is helps clarify it. This may seem overly simplistic, but you would be surprised how often we don't accurately frame the issue, which can limit our options for solutions. For instance, if your car is in need of a lot of expensive repairs and you are not certain if you want to fix the car or not, you may frame the decision as: "Should I fix the car or get a new one?" That is too narrow, especially if you live in an area with other transportation options. Re-framing the issue might bring new options. This particular issue might best be stated as: "Should I invest in fixing the car now, or are there other options?" The next step in this decision making process will elucidate the importance of correctly stating the issue.

Generate alternatives. What options do you have for solving this problem? This is where you want to brainstorm, and write down any solutions that come to mind, no matter how unrealistic they may seem. Spend some time on this step. Don't assume you can generate all the possible alternatives in one sitting. Sleep on it. Go for a walk or a run, so your mind can incubate on the issue and generate some creative alternatives. With the car example I mentioned in step 1, you might consider waiting to fix the car until you have saved some money or gotten a second opinion on the repair work needed, ride share for a while, sell the car and ride share for a while or permanently, sell the car and use public transportation, invest in a ride share program at work, trade the car in for a new or used vehicle before doing the repairs, do the repairs and then trade it in for a new or used vehicle, barter some of the cost of repairs, plan to do the repairs over time with the most urgent being done first, and then prepare a schedule for the remaining repairs with the help of your trusted mechanic. Do you live in a fair weather area, where you could use a bicycle instead of a car? This would possibly contribute to good health AND save money. This could also be a solution for a short period of time until you can afford the repairs, or come to another decision.

List the considerations (the pros and cons) for each alternative. Be realistic and thorough. What are the benefits and challenges for each alternative?

Gather information about each consideration. Take your time here to gather information that both confirms and disconfirms the soundness of some of your options. Avoid confirmation bias by looking at all of the information!

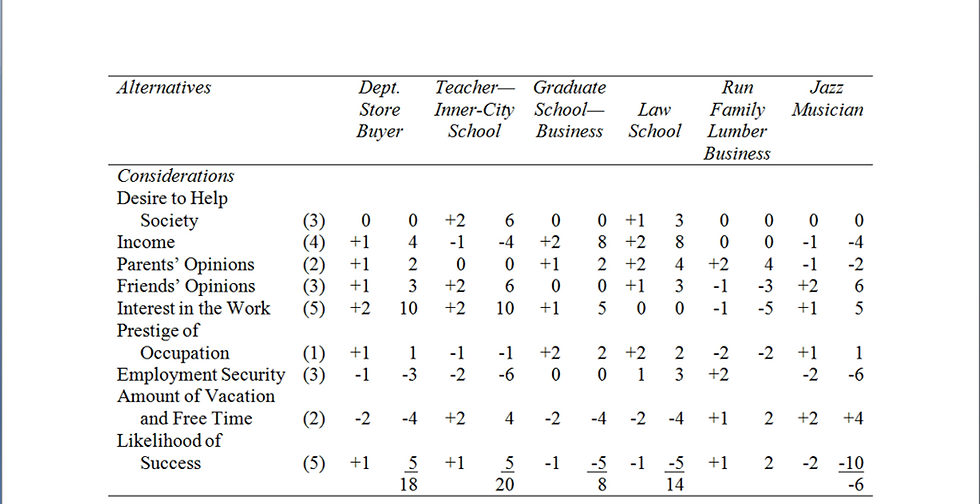

Weigh the alternatives and considerations. When you have only two options: yes or no, then this is the oft used strategy where you list the pros and cons for a solution, and decide 'yes' or 'no', based on whether the pro or con list is larger. I was raised with this strategy, but it has a major flaw: the assumption that each item in the pro or con list are equally weighted, or equally important. That is most definitely not true, which takes us to the next consideration....

Acknowledge whether you are a maximizer or satisficer. Maximizers, by definition, want to maximize the decision outcomes, and invest a lot of time (some would argue too much time) in the decision making process. Need to buy a new car? A maximizer is likely to pour over car reviews, car options and prices to find the best car with the coolest options for a good price. Sounds great, but research suggests that the joy you feel about the awesome new car is short lived. As soon as you see the next year's model, with new colors and upgraded options/technology, you feel far less satisfied with the choice you made. See a cooler version of your car on the freeway? Your satisfaction wanes, and you wish for the 'better' version. Barry Schwartz, a psychologist, coined the phrase the 'paradox of choice', in which he found from research that while we think we like options, too many options/choices can leave is paralyzed and indecisive, or filled with regret after we have made a choice. An interesting study of the paradox of choice observed purchasing behaviors of shoppers in a grocery store. The shoppers were given samples of flavored jams. In one instance, shoppers were given a small number of samples, say 3-4 flavors, and in another instance shoppers were given more, say 7 flavors. Researchers compared the two groups to see who was more likely to buy jam. The people in the 3-4 flavor sample group were more likely to buy than those in the 7 flavor sample group. Too many choices can be just that, too many. So, when we spend a lot of time looking over the options, like a maximizer is likely to do, we are at greater risk of regret. Satisficers, on the other hand, are more likely to be satisfied with their decision, and it is in large part due to their attitude about the outcome and the process of weighing options. For the satisficer, they are likely to look at the car buying process with a small list of 'wants'. Maybe a price range, and things like good mechanical history, high fuel efficiency and maybe a good sound system. Done. The first 1-2 cars that check off those items are enough to make a decision and satisfy the satisficer. Moral of the story, work toward being a satisficer, and think about the problem, alternatives, and the weight of the pros and cons through that lens. Then when you see someone with a newer, cooler version of the car you chose, you can shrug and remind yourself that you got what you wanted, so what pleases someone else is of less importance.

Make a decision. Look at the alternatives and the list of pros and cons for each one, after you have weighted each item on the pros and cons list (see example of weighted lists below). There is one more consideration to make here, after weighting, and that is intuition. If the weighted lists reflect two choices that are really close, and one 'feels' better than the other, listen to that intuitive response. It may mean that you didn't give enough weight to something on the list, but regardless, your intuition matters at this point. At this point in the process, that intuition is less about a reflexive bias, as you have spent some time and effort, theoretically, working through the decision, which would have likely uncovered your biases.

Now that you are familiar with the decision making process, I want to spend some time talking about some problems you might face in the process. Some things to avoid.

Failure to seek disconfirming evidence. Make sure you gather information that both supports and contradicts each of your options. Really set on the sports car? Think hard about that decision. Don't just look at the information that tells you how much fun you will have driving it. Look at the challenges that decision might bring: what if you need extra room for people or trunk space, what is the mechanical history of this car/model, and will it be functional in the climate in which you live? Thinking about moving to another state that looks beautiful? What might be some of the downsides of living there, and how would you weight those issues? Gathering all of the information, both pros and cons, will help you make a good decision and reduce the risk of regret and post-decision dissonance.

Feeling rushed to make the decision. This can be true if you are rushing yourself, or if someone else is pushing you to make a decision. If it is someone else, I would think about their motive for rushing you. Is it because they are concerned if you take more time to weight your options, you will make a decision they won't like? If you are rushing yourself, think about that for a moment. Why are you pushing yourself, and what are the inherent risks of rushing? Is there a small price to be paid for slowing down, which will help you make a good decision? Take your time.

Feeling overconfident. This can be about over confidence in framing the issue, or in your own knowledge of the options. Make sure to seek guidance, input, advice from other people. Big decisions are best made when we seek alternate perspectives. Someone else may have experience with that sports car that could help you make a decision. Or that state, or job, or company you are considering working for... you get the picture. It only requires one person to make a decision, but it takes a village to make a good one.

Wishful thinking. This is similar to overconfidence. Wishful thinking is the act, the mistake, of glossing over some of the difficulties or obstacles that might come from a particular alternative. Make sure you really think through each option realistically.

Psychological reactance. Pushing back on limitations. We don't like to be told we can't do something, and our human reflex is to push back. Tell me I can't have that car? Now I want it even more. Be careful!

Mere exposure effect. This I have mentioned before in earlier posts. The more we are exposed to something, the more likeable it seems. This may seem counter-intuitive. When you hear a commercial or a jingle over and over, you may get irritated by it. But, you also may find yourself humming that jingle when you least expect it. Heard that "1-877-CARS-4-KIDS- jingle enough to recite it from memory? You bet, but I bet it is the first thing that comes to mind when you have a car you want to get rid of quickly (not that I have ever had that problem). You get the point. Repeated exposure to any 'thing' makes it more appealing, more readily available to memory, more believable. Be wary of the mere exposure effect. It can be a trap to override your intuition or the energy-depleting process of making a good decision.

Liking or reciprocity. As human beings, we like to be liked, generally. It is embedded in our DNA to connect with others, and as part of the DNA, we also tend to reciprocate when someone does something nice for us. So, be wary of making a decision to seek someone's approval, or the desire to make a decision because you want to reciprocate a favor. Someone does something nice for you, great. That doesn't mean you have to vote for them, lend them money, say yes to a favor they ask of you. Only say yes if it is what you really want after careful consideration.

Emotional states. Our emotions can drive our decision making. Try not to make a decision when you are feeling an intense emotional response of any sort. Also, not when you are hungry or tired. All of these experiences can fog our decision making, which we may come to regret pretty quickly. Make a decision when you are clear headed. Fed, rested, not rushed, and are able to carefully weigh your options.

Don't rush out to adopt a puppy after watching those very emotionally laden ads about pet abuse. They are sad and powerful, and are created for just that reason. Adopt a puppy because you really want a life long partner, and you have given it a lot of thought.

On that note, I wanted a puppy last year after moving across the country to a new state, new job, new home, all by myself. It was a challenging change of circumstance and I thought a puppy would really help me. I waited, and I am glad I did. I waited an entire year, so I had established friendships, my career, and knowledge of my new community before diving into puppy life. I also spent a lot of time looking at breeds before deciding which type would be best suited for my home and would be a great trail running buddy. I hit the jackpot with 'Gussie', and she is so amazing. But I took the time to make a good decision after a lot of planning. So now, when she has an accident in the house, I know it is all part of puppy life, and I am not regretting my decision to get a puppy because I didn't rush into it!

There you have it. A nice list of steps to take in making decisions, and some advice on pitfalls to avoid in the process.

Whether it is how to vote in an upcoming election, whether to mask or not mask (is that still really a question?), what to do for the holidays during a pandemic, a job opportunity, a car, a vaccine, a peaceful protest, or a relationship... think about the decision making process, and practice using it. You will be glad you did, even if the outcome isn't what you had hoped it would be. I promise!

Be well, stay safe, and take care.

*tables from "Thought and Knowledge, An Introduction to Critical Thinking, 2013, Diane Halpern, Psychology Press

Comments